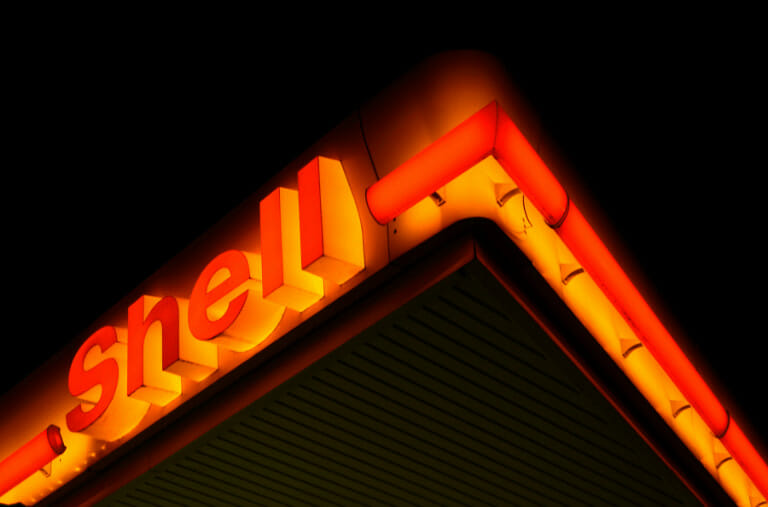

In a ground-breaking judgment, the UK Supreme Court allowed an appeal in a group litigation against the oil and gas company Shell plc.

The decision will allow 42,500 Nigerian victims to continue their fight for justice in England.

Quest for justice

Following a hearing held in June 2020, the UK Supreme Court last week allowed an appeal from the Court of Appeal’s decision in the case of Okpabi and others (Appellants) v Royal Dutch Shell Plc and another (Respondents) [2018] EWCA Civ 191.

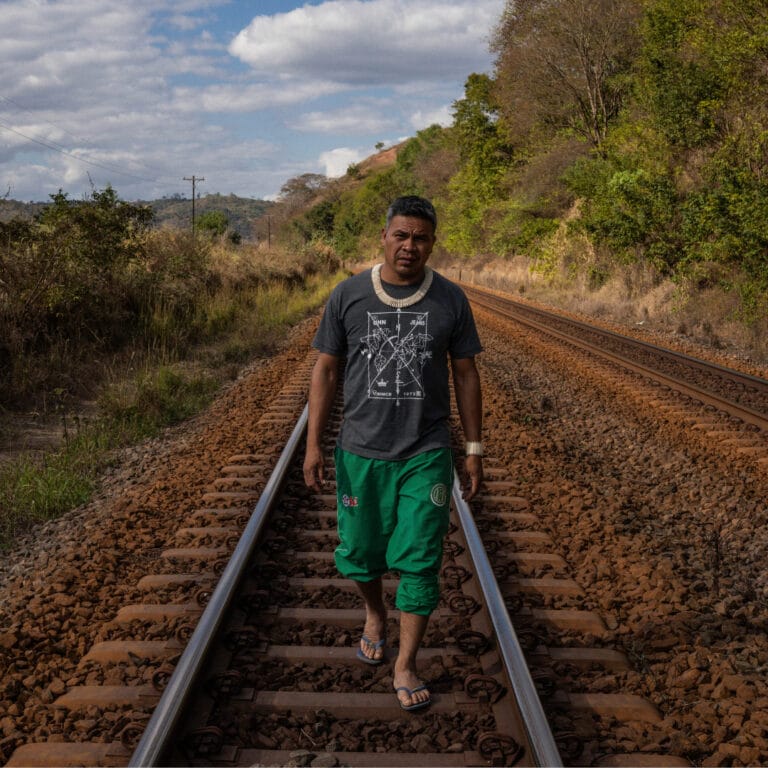

The ongoing litigation involves 42,500 individuals, all of whom are members of the Ogale and Bille communities in Nigeria, who have had their health and livelihood affected by ongoing pollution and environmental damage caused by oil leaks.

The oil leaks in the region where the victims reside emanate from oil pipelines and the associated infrastructure operated as part of a joint venture by one of the respondents.

Jurisdiction and duty of care

The appeal was concerned with the jurisdiction of the English courts against Shell Petroleum Development Company of Nigeria Ltd (“SPDC”), a Nigerian company, and with whether a common law duty of care was owed by the English parent company, Royal Dutch Shell Plc (“RDS”), to those affected.

The victims argued that the English company RDS owed them a duty of care because of the significant control RDS exercised over SPDC’s operations.

The Supreme Court found that there is, in fact, an arguable case for RDS having a duty of care and allowed the appeal.

Our lawyers offered a summary of the judgment, highlighting and analysing the key points.

1. Material errors of law

• Jurisdictional applications should not result in a ‘mini-trial’

The Supreme Court held that the Court of Appeal had wrongly conducted a “mini trial” and erred in its approach to the analysis of the evidence, contrary to the guidance provided by the Supreme Court in earlier cases, including Vedanta Resources PLC and another (Appellants) v. Lungowe and others (Respondents) [2019] UKSC 2.

According to the Supreme Court’s judgment in Okpabi, in jurisdictional applications aimed at determining whether there is a real issue to be tried between the parties, factual averments made in support of a claim should be accepted, unless they are “demonstrably untrue or unsupportable” [101-109].

• Use of group-wide policies and guidelines

In Vedanta, the Supreme Court had held that corporate governance documents are of fundamental importance in determining whether a duty of care is owed by a parent company in respect of the acts of its subsidiary.

In light of its earlier judgment in Vedanta, the Supreme Court in Okpabi ruled that the Court of Appeal had erred in ruling that the promulgation by a parent company of group wide policies or standards can never by itself give rise to a duty of care.

• Volume of evidence

The Supreme Court reiterated the importance of proportionality when deciding on jurisdictional issues and observed that filing large quantities of evidential material (over 2000 pages of evidence were relied on by the parties in Okpabi) was inappropriate [20-23].

• Control

The Supreme Court further ruled that the majority in the Court of Appeal dealt inappropriately with the notion of control.

Applying Lord Briggs’ approach in Vedanta, the Supreme Court held that the most relevant factor in this regard is whether the parent company effectively took over the management of its subsidiary in whole or in part.

Furthermore, the Supreme Court emphasised that a subsidiary might maintain de jure control of its activities, but “nonetheless delegate de facto management of part of them to emissaries of its parent” [147].

• Not a novel category of duty of care

Reaffirming its ruling in Vedanta, the Supreme Court clarified that the finding that a parent company can owe a duty of care for the activities of its subsidiaries is not based on a “distinct category of common law negligence” [25] and that the Court of Appeal had erred in this regard by applying the Caparo v Dickman test to the facts of Okpabi.

2. Implication for international litigation

The Supreme Court’s ruling in Okpabi, in line with its earlier judgment in Vedanta, demonstrates the potential for victims to seek redress from multinational companies headquartered in England for the wrongdoings of their overseas subsidiaries.

Whilst some jurisdictional issues remain outstanding in Okpabi, the ruling of the Supreme Court already reinforces the precedent set by Vedanta to the effect that the English courts will not hesitate to hold English-domiciled corporations responsible for the damage they caused to individuals and to the environment, whether in the UK or abroad.